About Project AZORIAN

Imagine standing atop the Empire State Building with an 8-foot-wide grappling hook on a 1-inch-diameter steel rope. Your task is to lower the hook to the street below, snag a compact car full of gold, and lift the car back to the top of the building. On top of that, the job has to be done without anyone noticing. That, essentially, describes what the CIA did in Project AZORIAN, a highly secret six-year effort to retrieve a sunken Soviet submarine from the Pacific Ocean floor during the Cold War.

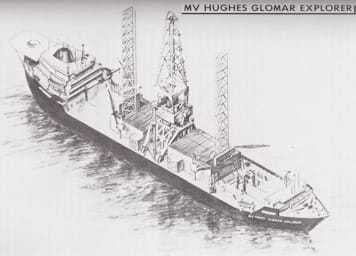

While the public believed the Hughes Glomar Explorer to be a vessel for deep sea mining, CIA was really using the ship to search for a sunken Soviet submarine.

The story began in 1968 when K-129, a Soviet Golf II-class submarine carrying three SS-N-4 nuclear-armed ballistic missiles, sailed from the naval base at Petropavlovsk on Russia’s Kamchatka Peninsula to take up its peacetime patrol station in the Pacific Ocean northeast of Hawaii. Soon after leaving port, the submarine and its entire crew were lost. After the Soviets abandoned their extensive search efforts, the US located the submarine about 1,800 miles northwest of Hawaii on the ocean floor 16,500 feet below. Recognizing the immense value of the intelligence on Soviet strategic capabilities that would be gained if the submarine were recovered, the CIA agreed to lead such a recovery effort with support from the Department of Defense.

CIA engineers faced a daunting task: lift the huge 1,750-ton, 132-foot-long portion of the wrecked submarine from an ocean abyss more than three miles below–under total secrecy.

While the public believed the Hughes Glomar Explorer to be a vessel for deep sea mining, CIA was really using the ship to search for a sunken Soviet submarine.

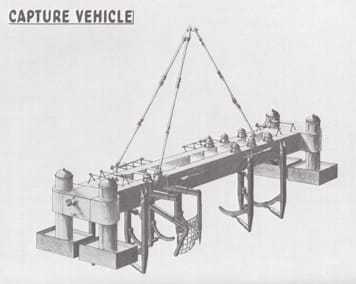

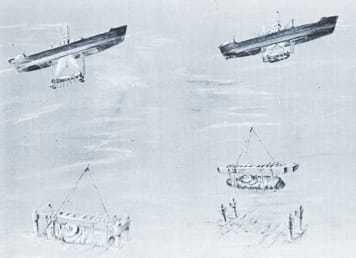

In 1970, after careful study, a team of CIA engineers and contractors determined that the only technically feasible approach was to use a large mechanical claw to grasp the hull and a heavy-duty hydraulic system mounted on a surface ship to lift it.

The ship would be called the Hughes Glomar Explorer, ostensibly a commercial deep-sea mining vessel ostensibly built and owned by billionaire Howard Hughes, who provided the plausible cover story that his ship was conducting marine research at extreme ocean depths and mining manganese nodules lying on the sea bottom. The ship would have the requisite stability and power to perform the task at hand.

While the public believed the Hughes Glomar Explorer to be a vessel for deep sea mining, CIA was really using the ship to search for a sunken Soviet submarine.

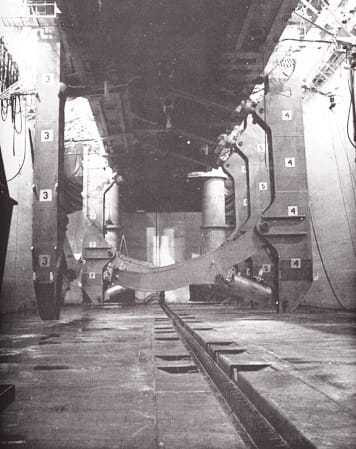

Constructed over the next four years, the ship included a derrick similar to an oil-drilling rig, a pipe-transfer crane, two tall docking legs, a huge claw-like capture vehicle, a center docking well (called the “moon pool”) large enough to contain the hoisted portion of the sub, and doors to open and close the well’s floor. To preserve the mission’s secrecy, the capture vehicle was built under roof and loaded into the ship from a barge submerged underneath. With these special capabilities, the ship could conduct the entire recovery under water, away from the view of other ships, aircraft, or spy satellites.

The heavy-lift operation was complex and fraught with risk. While maintaining its position in the ocean currents, the ship had to lower the capture vehicle by adding 60-foot sections of supporting steel pipe, one at a time. When it reached the submarine section, the capture vehicle then had to be positioned to straddle the sunken submarine section, and its powerful jaws had to grab the hull. Then the ship had to raise the capture vehicle with the section in its clutches by reversing the lift process and removing supporting pipe sections one at a time until the submarine was securely stowed in the ship’s docking well.

While the public believed the Hughes Glomar Explorer to be a vessel for deep sea mining, CIA was really using the ship to search for a sunken Soviet submarine.

Sailing from Long Beach, California, the Glomar Explorer arrived over the recovery site on 4 July 1974 and conducted salvage operations for more than two months under total secrecy–despite much of the time being monitored by nearby Soviet ships curious about its mission. The crew encountered many problems, some serious, but quickly overcame them, and the lift proceeded according to plan. However, when the submarine section was about halfway up, it broke apart, and a portion plunged back to the ocean bottom. Crestfallen, the Glomar crew successfully hauled up the portion that remained in the capture vehicle.

Among the contents of the recovered section were the bodies of six Soviet submariners. They were given a formal military burial at sea. In a gesture of good will, Director of Central Intelligence Robert Gates presented a film of the burial ceremony to Russian President Boris Yeltsin in 1992.

While the public believed the Hughes Glomar Explorer to be a vessel for deep sea mining, CIA was really using the ship to search for a sunken Soviet submarine.

Almost immediately after the disappointing recovery effort, planning began for a second mission to recover the lost portion. A bizarre and totally unforeseen occurrence, however, had already started a chain of events that would ultimately expose the Glomar Explorer’s true purpose and make another mission impossible. In June 1974, just before the Glomar set sail, thieves had broken into one of the Hughes offices in Los Angeles and stolen secret documents, one tying Howard Hughes to CIA and the Glomar Explorer. Desperate to recover this document, CIA called in the FBI, which in turn enlisted the Los Angeles Police Department. The search drew attention, and by the autumn of 1974 the media began to pick up rumors of a sensational story.

Director of Central Intelligence William E. Colby personally appealed to those who had learned about AZORIAN not to disclose the project. For a while they cooperated, but on 7 February 1975 the Los Angeles Times published an account that made connections between the robbery, Hughes, CIA, and the recovery operation. After that, investigative reporter Jack Anderson broke the story on national television, asserting that Navy experts had told him the sunken submarine contained no real secrets and that the project was a waste of taxpayers’ money. Journalists flooded into the Long Beach area where the Glomar was preparing for its second mission. The Ford Administration neither confirmed nor denied any of the stories in circulation, but by late June, the Soviets had assigned a ship to monitor and guard the recovery site. With Glomar’s cover blown, the White House canceled further recovery operations.

While the public believed the Hughes Glomar Explorer to be a vessel for deep sea mining, CIA was really using the ship to search for a sunken Soviet submarine.

The Glomar’s brief covert career was now over, and after some experimental ocean mining voyages sponsored by a consortium of industry leaders, it was mothballed for over a quarter century. Then in the late 1990s, a US petroleum company restored the ship for use in deep-sea oil drilling and exploration. Renamed the GSF Explorer, the ship is still being used for that purpose.

Although Project AZORIAN failed to meet its full intelligence objectives, CIA considered the operation to be one of the greatest intelligence coups of the Cold War. Project AZORIAN remains an engineering marvel, advancing the state of the art in deep-ocean mining and heavy-lift technology.

While the public believed the Hughes Glomar Explorer to be a vessel for deep sea mining, CIA was really using the ship to search for a sunken Soviet submarine.