About the OSS

Before World War II, the US Government left the business of collecting and disseminating intelligence to American foreign-policy experts and elements of the armed services. America’s entry into the war following the intelligence failure of Pearl Harbor led to the establishment of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) on 13 June 1942.

Snow suits like this one were worn by OSS’s Norwegian Special Operations Group during behind-the-lines ski-parachute sabotage operations in Norway during World War II.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed William J. Donovan, a highly decorated World War I officer, as Director of the OSS. Donovan organized the OSS to reflect his vision of a national intelligence center, uniquely combining research and analysis, covert operations, counterintelligence, espionage, and technical development–core missions of today’s Central Intelligence Agency.

OSS field officers often relied on their tactical training out in the field. Reading maps was a skill used during planning and executing operations.

Donovan’s Research and Analysis Branch, cornerstone of the OSS, made significant contributions to the Allied victory. Staffed by some of the best minds in America, the branch provided timely assessment of the Allied bombing campaign in Europe, studied operations in countries where Allied forces were fighting, and developed preparations for the occupation of Germany. Perhaps most importantly, the branch validated Donovan’s vision of a central all-source analysis capability by demonstrating that the greater part of vital intelligence could be obtained not by parachuting behind enemy lines but by poring through papers, cables, reports, photographs, maps, journals, foreign newspapers, and other materials–laying the foundation of modern intelligence research and analysis.

The OSS formed numerous “Operational Groups” to run American units behind enemy lines. These were small teams of specially trained US military commandos who fought in uniform with no obvious connection to the OSS (so they would not be shot as spies if captured). Knowledge of foreign language was essential. Training included parachuting, amphibious operations, skiing, mountain climbing, radio operation, and espionage tactics. Operational Groups fought in France, Italy, Greece, Yugoslavia, Burma, Malaya, and China, usually alongside partisan forces.

As clandestine equipment and concealments were often not readily available off the shelf, OSS frequently produced its own gadgets and weaponry for operational use.

The OSS joined paramilitary forces from Allied countries to form “Jedburgh” teams that parachuted into France to aid the resistance movement against German occupiers. A “Jed” team consisted of two to four men: some combination of an OSS officer, a British officer, a Free French officer or enlisted man, and sometimes a Belgian, Dutch, or Canadian soldier. More than 90 Jed teams parachuted into France in the summer of 1944 to support the Normandy landings by coordinating airdrops of arms and supplies and by conducting hit-and-run attacks and sabotage raids on the German forces.

OSS’s Detachment 101 served in Burma, recruiting, training, and supporting native Kachin tribesmen to collect intelligence and fight the Japanese occupiers. When Allied troops invaded Burma in 1944, Detachment 101 teams advanced well ahead of the conventional combat formations, gathering intelligence, sowing rumors, sabotaging key installations, rescuing downed Allied fliers, and snuffing out isolated Japanese positions.

To liberate Thailand from Japanese domination during World War II, the OSS launched the “Free Thai” movement. The OSS trained the best and brightest volunteer Thai students from universities across the US and dispatched them into Thailand by submarine, seaplane, parachute, and foot. There they made contact with the resistance, provided accurate intelligence on Japanese military deployments, rescued captured Allied soldiers, and prepared the ground for eventual Japanese surrender.

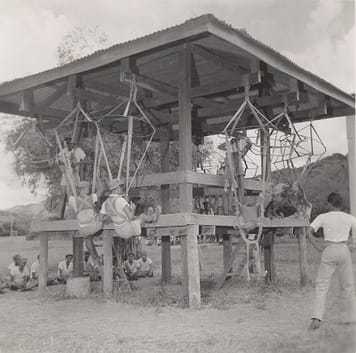

Successful OSS operations sometimes relied on joint efforts. Chinese counterparts were trained extensively on parachuting techniques by OSS’s Operational Group in preparation for action.

The best intelligence available to British and American commanders during World War II came from intercepted and deciphered enemy messages obtained through the ULTRA (German) and MAGIC (Japanese) Programs. In early 1943, Donovan created X-2, an elite counterintelligence branch with access to valuable ULTRA intelligence. X-2 personnel followed British security practices (more strict than those of other OSS elements) and operated somewhat independently to protect ULTRA. With this secret intelligence, X-2 guided OSS operations and developed innovative counterintelligence actions.

OSS activities created a steady demand for devices and documents that could be used to trick, attack, or demoralize the enemy. Donovan capitalized on the many British devices already developed and promoted an in-house capability to adapt them to OSS needs and to fabricate additional ones required for clandestine missions.

The OSS employed nearly 13,000 men and women at its peak and operated for a little more than three years, from 1942 to 1945. In that short time, it helped shorten the war and save lives in Europe, North Africa, and Asia. It left a legacy of daring and innovation that has influenced American military and intelligence thinking since World War II.

Today’s Central Intelligence Agency derives a significant institutional and spiritual legacy from the OSS. In some cases, this legacy descended directly: key personnel, files, funds, procedures, and contacts assembled by the OSS found their way into the CIA more or less intact. In other cases, the legacy is less tangible but no less real: the professionalization of intelligence, the organizational esprit de corps, the essential role of national intelligence in policymaking and war fighting. The CIA owes a debt of gratitude to the OSS and William J. Donovan, the charismatic leader and moving force behind it.

For videos about OSS, please click here.