I'm Rob Byer, the director of CIA Museum.

The CIA Intelligence Art Collection at Headquarters

Features artwork that reflects a broad range of activities by Agency officers at different times and places throughout its history.

What most people don't know is that two of the paintings in the collection are by a Directorate of Science and Technology officer Deborah Dismuke, the first Agency officer to be featured in the CIA Intelligence Art Program.

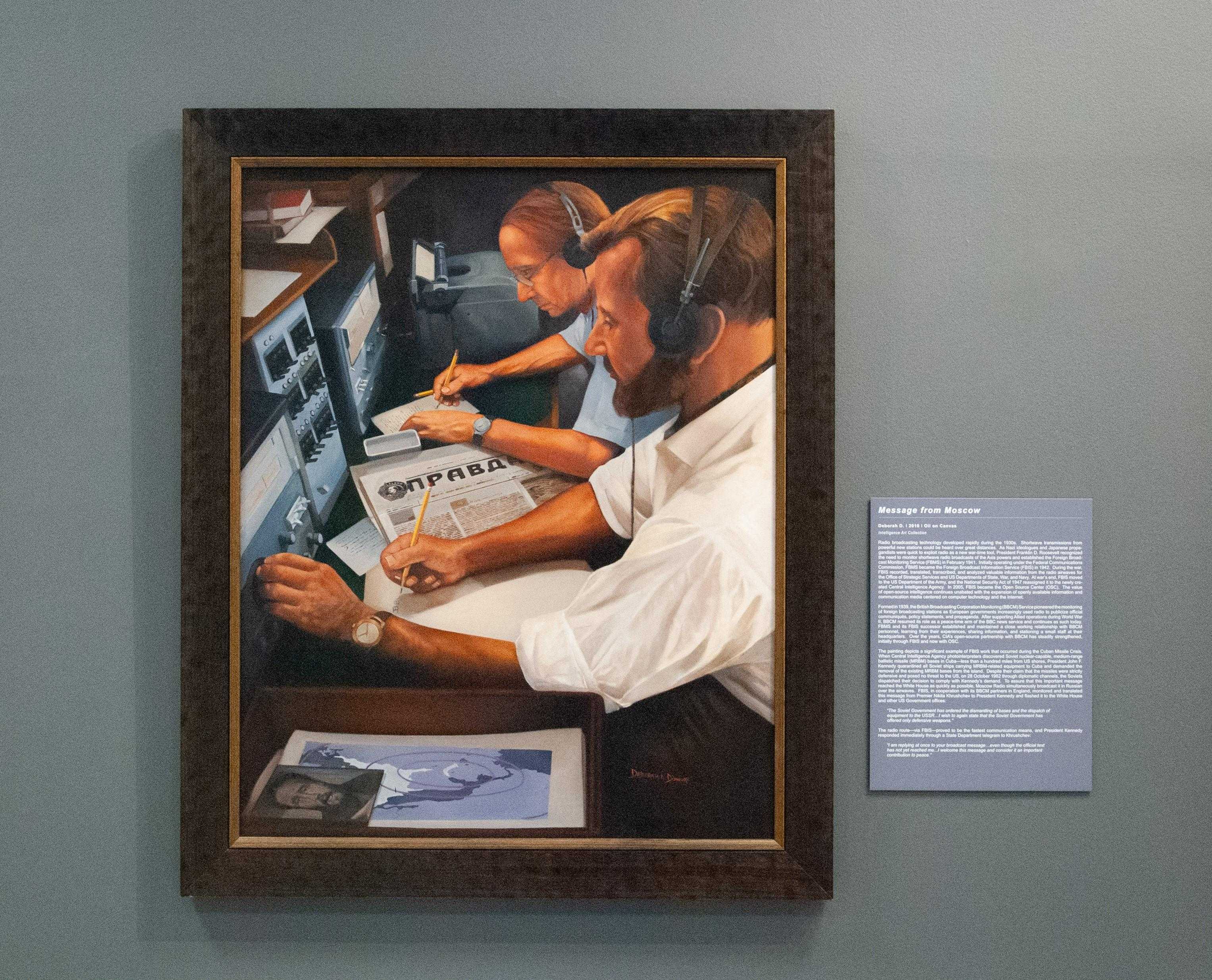

Message from Moscow is the first of Deborah's paintings to be commissioned by CIA in 2010.

The painting reflects a pivotal moment in the Cold War.

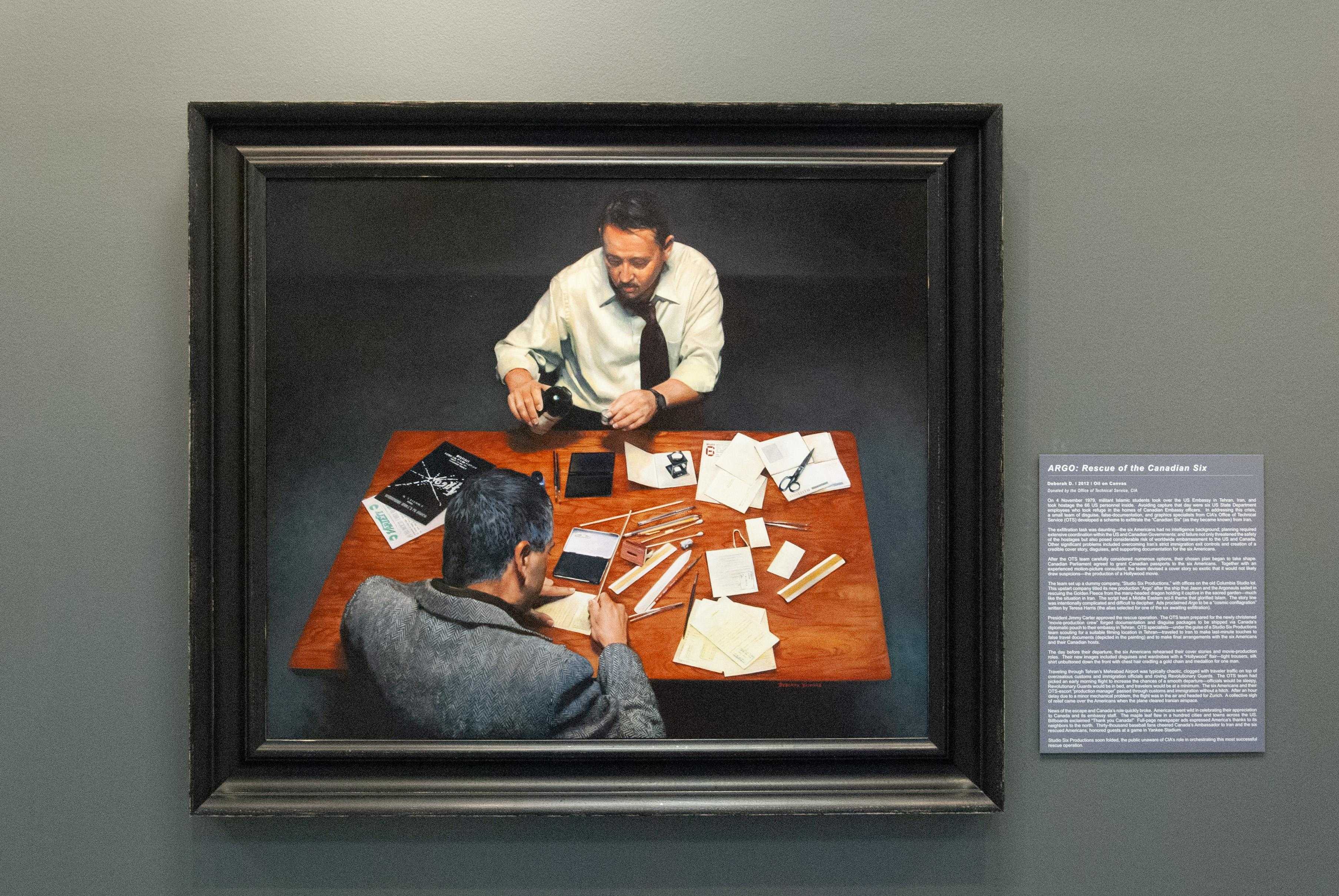

Her second painting, commissioned two years later, shows legendary officer Tony Mendez and Ed Johnson altering documents to ensure the escape of six Americans hiding in the homes of Canadian diplomats after the takeover of the U.S. Embassy in Iran.

Although Deborah's Agency work doesn't involve painting, she makes time to channel her passion and dedication to CIA's mission by creating art to inform, instruct and inspire.

Let's get to know Deborah Dismuke.

I do remember as I was growing up, I loved looking at pictures.

I got my first drawing lessons from a priest who studied in Italy.

So he would look at my drawings and then he would tell me, This is where we need to clean up and pay close attention to values and so on.

So I've learned a lot from him.

My background at first was painting, and I did get a senatorial scholarship from Senator Clarence Blount, and he said, "Let me be honest here.

If you study to be a painter, you're gonna starve." So I did change my major from being a painter to an illustrator and designer.

And I feel to this day, if I did not change, I would not have gotten into the CIA.

I got my first break at DS&T. It was called the George Methlie School.

We were looking to celebrate, you know, the opening of the school and we imagined it would be nice if we could do a portrait of him.

They had no idea that I was an artist that could do that.

I did a picture, a drawing of George Methlie and presented it to the director of the school, and she loved it.

I also did a drawing of John McComb.

The DS&T was celebrating their 50th anniversary, and at the time they were looking to see what mission the Agency has done that they want to highlight or focus on.

So they mentioned ARGO.

We were trying to figure out what would be the best scene or concept.

I believe it was like a day before that they were doctoring the documents and everything.

They had all the tradecraft there.

I could not go with full detail with his face, even though I get feedback from folks, oh my gosh, it looks like a photograph, but I cannot have the face look realistic and everything on the table is not.

It's more like impressionists using the vivid colors and the light, the darks and values.

I still had the look and feel of it looking realistic.

I know they put the unveiling of ARGO on hold till the Academy Awards night, and sure enough, I was watching the awards and it came in Best Picture and all.

And I went, "Oh, my gosh.

I can't wait to unveil this painting now."

And I was so excited that Tony was there.

Two of the folks that were hostages that was also there during the unveiling.

And I just felt so proud that this painting means so much and the mission and everything that happened, getting those hostages out, that captured that moment in time.

And for the two hostages and even Tony had mentioned, this is great.

You captured that moment in time, that piece of that puzzle to help these people, to board that plane, to get out of there.

So when you see those documents on the table was so important.

I felt that I captured something that was significant at that time.

It was huge.

Music drives my work.

When I'm doing projects for the Agency, I'm having fun.

I enjoy working, doing that, and sometimes I just lose track of time.

I look at the clock, it's like ten.

I have my music going, I'm working on it, and next thing I know, it's like four in the morning.

To be the first staff officer and African-American woman to have my work displayed in the art gallery was huge because I never - it didn't dawn on me till Toni Hiley had mentioned, you know what this means?

I mean, this is huge.

Wait, what?

This is really cool.

Deborah Dismuke embodies the spirit and dedication of CIA with a humble demeanor that belies her immense talent.

CIA Museum and CIA's Fine Arts Commission are proud to feature her work in the halls of this agency that further the museum mission to inform, instruct and inspire.

[MUSIC]

Every day officers crisscross the corridors of CIA Headquarters thousands of times passing historic intelligence artifacts and paintings on display. Many walk past on the way to their office or a meeting. Others stop to admire. Everyone who has been at the Agency for some time is familiar with the art and the missions they depict, but not everyone knows the artists behind the works—or that two were painted by CIA’s own, Deborah Dismuke.

When Deborah picked up a paintbrush as a child, she never imagined that she would one day join the CIA let alone earn the distinction of being the first officer, first African American, and first woman, to have her work featured in the Intelligence Art Gallery inside its Headquarters. Her works are a snapshot in time of key intelligence figures or intelligence in action, shaping the course of history.

Deborah’s passion for art began while growing up in Charlotte, North Carolina. “I was an introvert as a child. Extremely quiet,” she shared. “I was taught by my mother at an early age how to draw basic shapes. I would experiment using crayons, colored pencils, and chalk. Early on, I found I could express myself creatively in ways that my words could not.”

As a young woman, Deborah studied at Maryland Institute College of Art. There, she learned that the CIA sought artists for its national security mission. She joined the Agency in 1987.

“The first job I held at CIA was as a Visual Information Specialist. My job was to design, produce, and finish static visual information projects supporting analysts working critical national security issues. Many of my designs were seen by senior policymakers and others across the Intelligence Community.”

All artists get inspiration from their unique life experiences and way of seeing the world around them. For Deborah, it is the perspective of intelligence work.

In 2012, CIA’s Intelligence Art Gallery showcased the first painting done by an officer. This honor went to Deborah, who titled the painting, “Message from Moscow,” which captures a critical moment during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis.

“Message from Moscow” depicts employees of the British Broadcasting Corporation Monitoring (BBCM) service translating Soviet Premier Krushchev’s Moscow Radio announcement that the USSR would comply with President Kennedy’s demand to dismantle its nuclear missile bases on Cuba after U-2 overflights of Cuba made the discovery less than 100 miles off of U.S. shores.

CIA unveiled another of Deborah’s paintings, “ARGO – Rescue of the Canadian Six,” in 2013 to commemorate the daring mission that exemplifies the Agency’s creativity and reliance on foreign and domestic partnerships.

“ARGO—Rescue of the Canadian Six” depicts two cover operatives—Tony Mendez and Ed Johnson (whose identity was only revealed recently, 44 years after the Argo operation)—from CIA’s Directorate of Science & Technology falsifying cover documents to pass to the Americans ahead of the sensitive exfiltration of six U.S. diplomats from Tehran.

In 2014, Deborah watched the 2002 film Windtalkers, which inspired another painting in her personal collection, “The Navajo Code Talkers.” She secured permission to use an old black and white photo of code talkers to recreate the oil painting, a process that entailed painstaking research to find the correct color pallet.

“The Navajo Code Talkers” depicts two Navajo Code Talkers who helped the U.S. Marine Corps during WW2 create an unbreakable code using the Navajo language, which was unintelligible to most. The hundreds of enlisted Navajo saved countless lives and hastened the war’s end though their honorable service was not widely known until after it was declassified in 1968.

This past year, Deborah created a portrait of William “Wild Bill” Donovan, the strong-willed WW1 hero who headed the Office of Strategic Services (OSS)—CIA’s wartime predecessor—from 1942-45 and fiercely lobbied for a permanent U.S. intelligence body. “I chose to do this painting of Donovan because he was involved in the creation of the OSS. I wanted to create a collection for myself, recognizing various people who were either part of CIA and its history or associated with intelligence efforts that made a huge difference in the world.”

Portrait of William Donovan

Deborah, now retired, has held multiple positions within the Agency throughout her career that tapped into her creative talents—at home and abroad. These days, Deborah reflects on her life’s work and everyone who has supported and inspired her along the way. “The people I most admired and shaped my life are teachers, painters, illustrators, photographers, actors, screenwriters, and composers. When I am in front of my canvas, I hear and see them all as I’m painting.”

“Painting provides me a sense of calm. It is my ‘safe place,’ my decompression zone. Just like some people find that keeping a journal or diary is good for their well-being, I feel that creating art or music is also good for a person's well-being. It enables me, an introverted person, to tell stories on canvas without having to express myself verbally because sometimes I am uncomfortable doing that. So, just as some people say ‘actions speak louder than words,’ I use my art to speak for me and to speak to people.”