Have you ever wondered if the state-of-the-art, advanced technology developed by CIA could ever be made available to the public? You may be surprised to learn that it already has.

Since our founding 75 years ago, we have developed technologies so advanced, they are often decades ahead of what is being created in the private sector. Although we develop secret technologies to help in our mission of intelligence gathering and analysis, sometimes these technologies can be declassified and released to the private sector so that they can benefit the public at-large. The lithium-iodine battery and Google Earth are just two examples.

Below are a few of the many technologies we developed, or helped to develop, that have made their way out of the shadows and into the public sphere.

* * * * *

Lithium-Iodine Battery

In the 1960s, researchers in CIA’s Directorate of Science and Technology created the (now commonplace) lithium-iodine battery to improve the longevity and performance of surveillance equipment and reconnaissance satellites. Certain operational missions required long-lasting batteries of various shapes and sizes.

In the early 1970s, CIA passed the technology to the medical community where it was used in heart pacemakers.

Today, most of your electronic devices have lithium-ion batteries in them: mostly likely including whatever device you’re using to read this right now.

Pacemakers, cell phones, and digital cameras all rely on technology CIA developed.

Google Earth

In February 2003, the CIA-funded venture-capital firm In-Q-Tel made a strategic investment in Keyhole, Inc., a pioneer of interactive 3-D earth visualization and creator of the groundbreaking rich-mapping EarthViewer 3D system.

CIA worked closely with other Intelligence Community organizations to tailor Keyhole’s systems to meet their needs. The finished product transformed the way intelligence officers interacted with geographic information and earth imagery. Users could now easily combine complicated sets of data and imagery into clear, realistic visual representations. Users could “fly” from space to street level seamlessly, while interactively exploring layers of information including roads, schools, businesses, and demographics.

The popularity of this technology eventually caught the attention of Google, which acquired Keyhole in 2004. You know this technology today as Google Earth.

Breast Cancer Detection

CIA’s advanced image-processing techniques used to identify missiles is also used to help fight breast cancer.

In 1994, CIA provided technology originally developed for the analysis of satellite imagery to the medical community to improve early detection of breast cancer. CIA and our Intelligence Community partners developed computer programs that detected changes in aerial imagery to identify, for example, new roads or missile sites. That same technology, it turned out, could be used in mammography analysis.

Specifically, the technique involved aligning and comparing digital x-ray images taken over time to identify any changes. These results were particularly helpful in diagnosing breast cancer in women under 50, where diagnosis is especially difficult. The use of these methods is believed to have considerably reduced the number of deaths from breast cancer.

Digital X-ray Detector Panel

Landsat Satellite Spectrometry

In 1996, CIA shared with the Navajo Nation satellite technology to help map the terrain and vegetation of their 27,000-square-mile reservation, which is the largest Native American reservation in the U.S., encompassing portions of Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah.

The technology, known as Landsat satellite spectrometry, helps produce digital maps that can tell the difference between various kinds of terrain and vegetation. The Navajo Nation’s terrain is sparsely vegetated, and the ability to map their terrain in detail allowed them to better “understand, reclaim, preserve, and protect their precious natural resources,” according to Mike Benson, then-spokesman for the tribal water resources department.

CIA originally developed this technology to gain in-depth understanding of desert terrains abroad.

Trace Metal Detection

During the Vietnam War, when the U.S. military and CIA went into civilian areas, they needed a way to determine who was an insurgent and who was a civilian. Guerrilla fighters, however, often tried to blend in with the villagers, making identifying them a challenge.

To tackle this problem, CIA developed what became known as trace metal detection—basically the ability to tell what kind of metal a person has handled, including guns. And, unlike gunshot residue tests (which CIA also helped develop) trace metal detection could detect if the subject merely handled the gun, not just if they fired a gun.

This early form of forensic analysis was shared with law enforcement and police departments around the U.S., who were interested in the new technology for their crime labs. Trace metal detection has been a useful tool used in many criminal investigations—including arson, homicide, suicide, and robbery—to forensically connect a gun, or other metal object or weapon, to an individual.

Identi-Kit

CIA developed the Identi-Kit to assist in sketching the face of a person of interest based upon witness recollections.

The kit breaks a full-face image into component parts: hair, brows, eyes, nose, lips, chin-line with ears, and age lines, plus beard, hat, and glasses, if any. It contains several dozen transparent slides picturing each of these components with different types of contours, 500 slides in all, with five notches on the side for different placements of each feature. From the kit’s catalog of slides, a witness selects those that best portray the subject person’s facial characteristics. The resulting image is not a finished portrait but a reasonably good line-drawing of distinctive physical contours.

A key benefit of the kit is the ease with which it permits a sketch to be sent quickly via telephone using only slide codes that enable reconstruction of the sketch with another kit. The kit also provides a standardized set of facial descriptors that may be used in identifying a wide spectrum of individuals.

After intelligence officers thoroughly proved Identi-Kit’s utility in many real-life operations over the years, CIA released it to police forces for use in apprehending criminals.

Custom Prosthetics

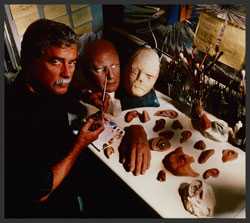

A non-traditional way that CIA has helped make a significant impact on the world is through one of its former employees. Robert Barron, a currently certified clinical anaplastologist, honed much of his natural artistic talents during his work as a CIA disguise specialist.

In 1983, Barron attended a conference held by the Association of Biomedical Sculptors. He was there to find out if the commercial world had any new materials to offer for disguise creation. In addition to discovering that the Agency was ahead of the commercial world in research, Barron discovered something life-changing: his second career.

“I saw all these people who had become disfigured by cancer and accidents and what prosthetics did for the quality of their life,” Barron said. “I thought to myself, ‘Bob, if you can change someone’s identity, you could certainly give back a disfigured person’s identity by designing prosthetics.’”

Having retired from CIA in 1993, Barron now works with medically disfigured patients to improve their confidence and restore their sense of identity by designing prosthetics tailored specifically for each patient. Barron credits his time at the CIA as the foundation for his second career. “My work with disguises is what led me to where I am now.”

After retiring from CIA, Bob Barron leveraged his unique skillset to design custom prosthetics for patients who needed them. Here, Bob works on a prosthesis in his lab. (Photo courtesy of Robert Barron)

CIA and Technology Today

These are just some of the incredible technologies CIA helped develop. If you’d like to learn more about how CIA is innovating today, and some of our private-public partnerships, including our newly created CIA Labs, check out this recent column from our very own “Ask Molly.”

The next time you are exploring a new land from the comfort of your laptop or snapping pictures with your lithium battery-powered smart phone, remember that technologies we rely upon daily often originated from unexpected places, including the CIA.