In Part Two of our Glorious Amateurs series (read Part One here), we focus on the amazing contributions of the women of OSS. Some of their stories have achieved star status, while others are just waiting to be told. Many of us are familiar with the accomplishments of OSS women like Virginia Hall and Julia Child, but have you ever heard of the southern socialite who became the first American female prisoner of war? Or the woman who escaped Nazi-occupied Austria to join the OSS? And how about the Slovak schoolteacher who was awarded the bronze star for helping OSS and British agents escape Nazi-occupied territory?

Early in the creation of the OSS, General William Donovan saw the potential of adding female spies to his growing pool of talent. Of the 13,000 personnel that made up the OSS, more than 4,000 officers were women, and they created propaganda, interrogated German prisoners, decoded intelligence, stole secrets, provided analysis, and engaged in counterintelligence. And they did all this while putting themselves in harm’s way–in every theater of World War II.

Here are just a few of the amazing stories of the sisterhood of spies.

Corporal Barbara Lauwers receiving the Bronze Star in Rome: April 1945

Barbara Lauwers and the “League of Lonely War Women”

Born in Czechoslovakia, Barbara Lauwers not only had a law degree, but was also a journalist who happened to be fluent in English, German, Czech, Slovak, and French. As the war broke out in Europe, she and her husband moved to the United States. After Pearl Harbor, her husband joined the US Army and Barbara started working at the Czech embassy in Washington, D.C. before eventually joining the Women’s Army Corps (WACs).

Stationed in Rome, with her knowledge of languages and being Czech herself, she worked with OSS’ Morale Operations Branch. During her time with the Branch, Barbara became the driving force in many successful propaganda campaigns.

Operation Sauerkraut

One of the most successful black ops of the war was called Operation Sauerkraut. Barbara and OSS agents would go into Allied POW camps, interview and select German or Czech POWs, train them and dispatch them back across the line to spread propaganda. These recruited former POWs were nicknamed the Sauerkraut agents.

Barbara also created The League of Lonely War Women. This mythical organization was created to demoralize German troops by making them believe that the German wives and girlfriends they left behind were having casual affairs with foreign men. Forged leaflets in German were printed in Rome and more than 200,000 copies were produced. This operation was so successful that even The Washington Post was fooled and ran a story entitled: “German soldiers on leave from the Italian front have only to pin an entwined heart on their lapel during furlough to find a girlfriend.”

The leaflet included this supposed plea from the women of Germany:

“We, of course, are selfish too—we have been separated from our men for many years;

With all those foreigners around us, we would like once more to press a real German

Youth to our bosom;

No inhibitions now: Your wife, sister, or lover is one of us as well;

We think of you and Germany’s future.”

On April 6, 1945, Barbara Lauwers was awarded the Bronze Star for getting nearly 600 Czechs to surrender to the Allies. She will be remembered for running some of the most successful campaigns in the Morale Operations Branch.

Gertrude Legendre: heiress, explorer, socialite, and spy

The Socialite who Outsmarted the Nazis: Gertrude Sanford Legendre

Gertrude Sanford Legendre lived a life most people could only dream about. Born into a wealthy South Carolina family, Gertrude was the sister of internationally known polo player Stephen “Laddie” Sanford and socialite Sara Jane Sanford. The family was so well known that playwright—and family friend—Phillip Barry modeled his 1929 play, Holiday, on the Sanford family. Two movie versions of the play followed; the latter, made in 1937, starred a young Katherine Hepburn as Gertrude.

While still in her teens, Gertrude embarked on her first hunting trip, traveling to numerous destinations around the world: Africa, Iran, and Southeast Asia. She also made a few stops closer to home—Canada, the Grand Tetons of Wyoming, and Alaska. Many of the specimens she collected on her travels were sent to the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. She also found plenty of time to party in the south of France with Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald—not to mention a certain Ernest Hemingway. During her travels she found a kindred spirit, and future husband, in explorer Sidney J. Legendre.

When World War II broke out, both Gertrude and her husband wanted to serve their country. Gertrude got a job with OSS in Washington, D.C. as a clerk managing a cable desk. But Gertrude was later transferred to Paris, giving her a WAC uniform and paperwork identifying her as a second lieutenant.

Gertrude Legendre: “I don’t contemplate life, I live it!”

“I am just a woman.”

In late September 1944, she became the first American woman in uniform to be captured in Germany during an unauthorized visit to the front near Luxembourg (it was rumored she was looking to meet up with old friend George S. Patton). As they approached the front, Gertrude, along with two OSS officers and their driver, ended up being pinned down by sniper fire and were forced to surrender.

Gertrude was held prisoner by the Germans for six months. Early on in her capture, she concocted a story that she was nothing more than a Red Cross volunteer who had hitched a ride with the soldiers.

After all, she told them, “I am just a woman.”

Gertrude never broke under interrogation and the Germans finally bought her story.

After months of waiting, she finally found an opportunity to escape while she was being moved to another camp by train.

As the train she was on drew closer to the Swiss border, she—in a bold move straight out of a World War II action movie—jumped off the train and landed near a forest. The German guards—stunned by what they had just seen—ordered her to stop, threatening that they would shoot. But Gertrude ignored them and ran away, securing her freedom.

Later, after hearing about her dramatic escape from behind enemy lines, the OSS sent her back to the States—with strict instructions not to tell the story of her capture to anyone.

After the war, Gertrude continued to pursue her travels around the world. She later turned her ancestral home, Medway, into an environmental trust to manage the land and teach conservation.

As someone who loved the finer things in life, she continued to live the opulent life of a socialite up until her passing away at age 97. A true bon vivant, she would always end her annual New Year’s Eve parties with the same toast: “I look ahead. I always have. I don’t contemplate life. I live it, and I’m having the time of my life!”

Maria Gulovich receiving the Bronze Star at West Point, 1946.

The Schoolteacher That Saved Lives: Maria Gulovich

In 1944 in German-occupied country of Slovakia, a 23-year old female schoolteacher was asked by a Jewish friend if she could hide his sister and her five-year-old son. This would mark the beginning of Maria Gulovich’s amazing journey with the underground resistance during World War II.

It wasn’t long before rumors that Maria was hiding the Jewish mother and son began to circulate. It was reported to Slovak authorities. Luckily for Maria, the Slovak Army captain sent to question her was secretly a member of the anti-fascist resistance. The Slovak officer found a new hiding place for the woman and son and recruited Maria, who spoke five languages, as a courier and translator for the resistance.

Working with the OSS, Operation DAWES, and “The Great Escape”

After a time working with Russian Intelligence, Maria was introduced to American OSS officers who had been sent to assist the Slovak uprising and rescue downed American airmen (Operation DAWES). Maria had never been comfortable working with the Russians, so when the OSS offered her an opportunity to work with the Americans, she jumped at the chance. Little did she know the challenges she would face.

A book chronicling Maria’s wartime exploits was published in 2008.

In October of 1944, the German Army crushed the Slovak uprising, and Maria, along with Soviet, American, and rebel troops fled to the mountains.

With her perfect German, Maria was able to obtain provisions, shelter and intelligence as they sought to escape German-occupied territory. As winter arrived, however, Maria and the Americans were caught in a blizzard on Mt. Dumbier, the highest mountain in central Slovakia.

The group found a hunting lodge and after a time Maria, along with two OSS officers and two British airmen, left the lodge to search for food and medical supplies. While they were gone, the Germans raided the hunting lodge and captured the Americans who had stayed behind. Some of the captured prisoners were sent to a concentration camp, while others were executed on the spot.

Maria and the four men advanced towards the Eastern front to avoid capture. It would take the five of them nine weeks to get to safety, during which time they were constantly on the move. Maria’s foot became seriously frostbitten from the time spent roaming around in frozen conditions, but she refused to stop, fearing they would be captured. The group ultimately made it to Bucharest, Romania, in March of 1945, and were eventually flown to OSS headquarters in Italy.

After the war, General Donovan personally arranged for Maria to immigrate to the United States. To acknowledge her dedication and acts of courage, Donovan awarded her the Bronze Star for bravery during a ceremony at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York, in 1946.

Cultural anthropologist Cora Du Bois at the time of her work with OSS.

Partners in OSS and in Life: Cora Du Bois and Jeanne Taylor

Born to Swiss immigrant parents in New York City in 1903, Cora Du Bois became interested in anthropology while earning a M.A. in history from Columbia University. Cora then traveled to the American Southwest to pursue further research in anthropology—studying several Native American tribes in Northern California and the Pacific Northwest.

Being a restless soul, her intellectual curiosity and dedication to research would eventually take her to Alor, a remote island off the coast of Indonesia, where she immersed herself deeply into the study of the local people and their culture. Her fieldwork focused on how the perception of behavior differs cross-culturally, and it wasn’t long before her work was noticed by legendary OSS Analyst, William Langer.

In 1944, the OSS reached out to Cora, and she agreed to join to help with the war effort.

Cora Du Bois giving her expertise to British Supreme Allied Commander Mountbatten (left).

During the war, Cora became the OSS area expert on Indonesia. Her management skills along with her dedication to research and analysis resulted in her promotion to Chief of Research & Analysis in the Southeast Asia Command. That assignment would take her to Kandy, Ceylon (modern day Sri Lanka) where Cora and her team provided vital information for the planning and execution of many OSS operations in Southeast Asia.

What Cora didn’t know was that she’d soon meet someone who would change her life forever.

Jeanne Taylor (left), Cora’s brother Gerard, and Cora Du Bois later in life. 1980.

A Life-changing Meeting in Ceylon: Enter Jeanne Taylor

Born in Saint Paul, Minnesota in 1912, Jeanne Taylor always dreamed of being an artist. She followed her dream while studying at the St. Paul School of Art and the Art Students League of New York.

During the 1930s, she was a supervisor for the Index of American Design for the Works Progress Administration (WPA) working in graphic design.

In 1944, while serving in OSS, Jeanne was sent to Ceylon as a graphics designer. And that is where she first met Cora. The two became an inseparable pair while working closely together, and they soon fell in love.

After the war, the couple stayed together in New York City, where Jeanne worked in graphic design and Cora continued her academic work in anthropology.

In 1953, Cora was informed that she had been awarded the Harvard-Radcliffe Zemurray Professorship, a position granting her full professorship with tenure in Arts and Sciences—the first of its kind to be offered to a female faculty member at Harvard.

Cora and Jeanne would remain loving lifelong companions. Cora passed away in 1991, and Jeanne, one year later in 1992.

OSS and CIA officer Cordelia Dodson Hood.

A First Hand Witness to the Nazi Horror: Cordelia Dodson

In March of 1938, 25-year old American student Cordelia Dodson was in Vienna, Austria pursuing graduate work in German language and literature. She happened to be attending the opera in the evening of March 11, 1938, when Hitler’s troops invaded Austria.

She knew right then and there that her world would change forever.

As Cordelia would later say of that time: “Things just happened so fast. All of our civilian rights, the police system, and certain protections that everyone took for granted were just gone. I learned to hate the Nazis from that time on. They were so arrogant, so merciless, rounding up anti-Nazis all over town. Their persecution of the Jews was inhuman. It was all too much.”

She returned to the States and continued her studies, graduating from Reed College in 1941.

As the US entered World War II, Cordelia joined the war effort after seeing the horror of the Nazis first hand. She accepted a job with US Military intelligence, translating and analyzing air order of battle at the Pentagon. When she requested a transfer overseas she was turned down, so she resigned and joined the OSS.

Shortly after joining the OSS, she was assigned first to London, England, and then Bern, Switzerland, where she worked with future CIA Director Allen Dulles.

Cordelia also served in the top secret X-2 group, doing counter-intelligence work as well as handling sensitive international monetary transactions—and tracing deposits of Nazi gold.

Constantly traveling between England, France and Switzerland, she flew on numerous dangerous secret night flights. On one flight she found herself escorting Swiss nationals with German prisoners of war on the plane.

“So many things I did at that time I did without thinking,” recalled Cordelia, years later. “I just didn’t have time to think about fear.”

But there was a silver lining to her exhausting back-and-forth travel. On one of her trips to Switzerland, she met her future husband, fellow OSS officer William J. Hood.

Following the war, the couple stayed in Vienna and joined the newly-formed CIA. Cordelia and William eventually divorced, but Cordelia remained with the Agency, working in various locations in Central and Western Europe, until her retirement in 1980.

Betty McIntosh (middle) and Doris Bohrer (right) being interviewed by Ann Curry for NBC news. 2013.

The Golden Girls of Westminster at Lake Ridge: Doris Bohrer and Elizabeth “Betty” McIntosh

The Lady with the Hand Grenade: Doris Sharrar Bohrer

Doris Sharrar was still a teenager when her family moved from Basin, Wyoming to Silver Spring, Maryland where her father had accepted a government job with the Veterans Administration. She graduated from Montgomery Blair High School in 1940. Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Doris took the Civil Service exam, and then found herself in the typing pool of the newly-created OSS.

Doris was assigned to clerical work typing intelligence reports, where many newly-minted OSS female employees started, but Doris wanted to do more and quickly advanced. She was selected to attend photo reconnaissance school and was soon posted to Egypt. There she helped to create balsa-wood relief maps of Sicily as the Allies prepared to invade Italy.

Doris continued working in aerial intelligence, gathering information about German military movements and locations of arms factories. She was posted to Bari, on the Adriatic coast, working jointly with the 15th Air Force.

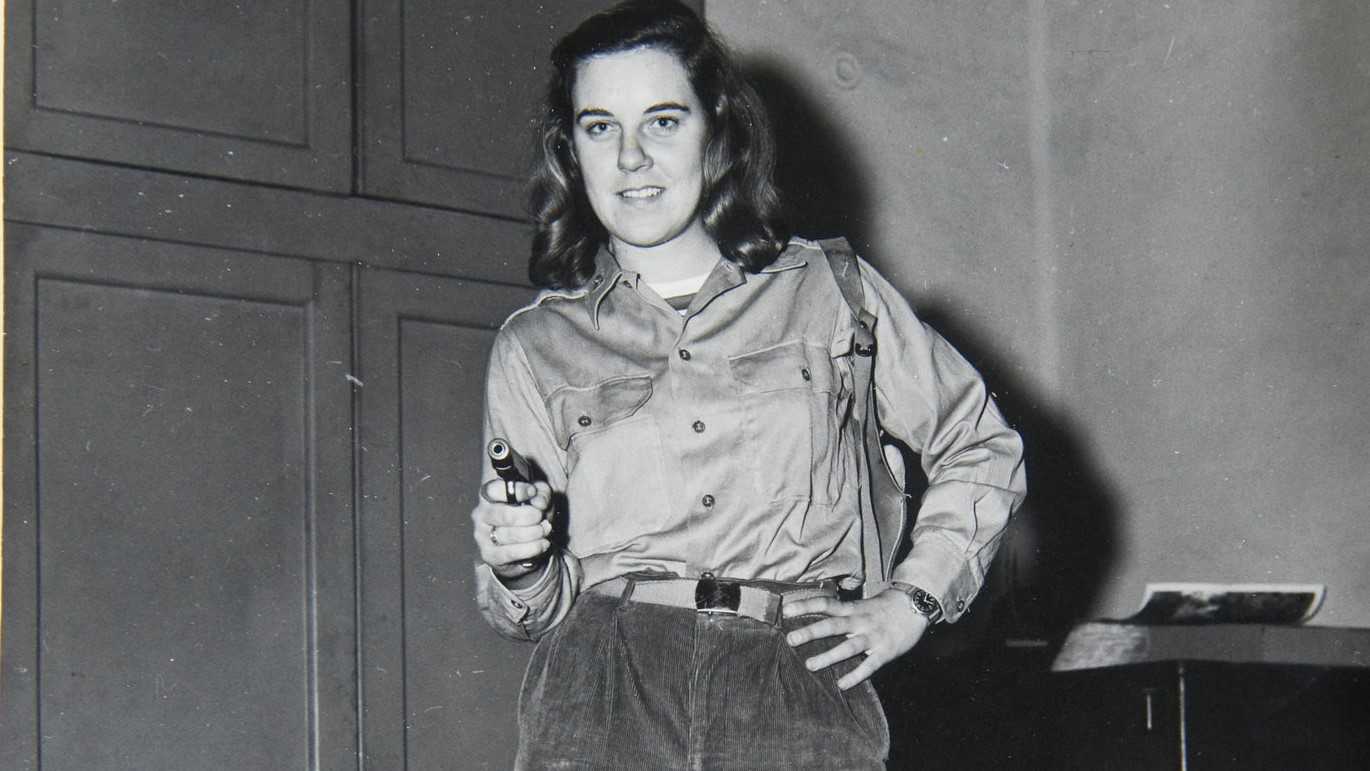

Doris Sharrar in Italy, 1944

Surrounded by military men with side arms, who teased and mocked her for being a female “spy”, Doris asked to carry a side arm as well. At first the military turned down her request, but eventually relented and issued her a weapon. She also asked to carry a hand grenade, as many of her military cohorts did at the time. When her request was denied, she had an engineer friend fashion a dud grenade, which she displayed while eating in the mess hall one day. An officer who happened to see the dud grenade demanded that she turn it over to him. Doris refused, and slammed it on the table while reaching for the pin—making all the men in the mess hall jump out the windows. Smiling, Doris sat back and continued eating her lunch in peace.

Doris met her husband, OSS officer Charles Bohrer, while serving overseas, and after the war the couple joined the newly-created CIA. After many years of dedicated service, she retired in 1979 as deputy chief of counterintelligence. In the 80s and 90s, she switched gears and sold real estate in Old Town, Alexandria. She also bred and raised prize-winning poodles on the side. Charles passed away in 2007, and two years later, she moved to the retirement village of Westminster at Lake Ridge—where she would meet a fellow widow and OSS alum Elizabeth “Betty” McIntosh.

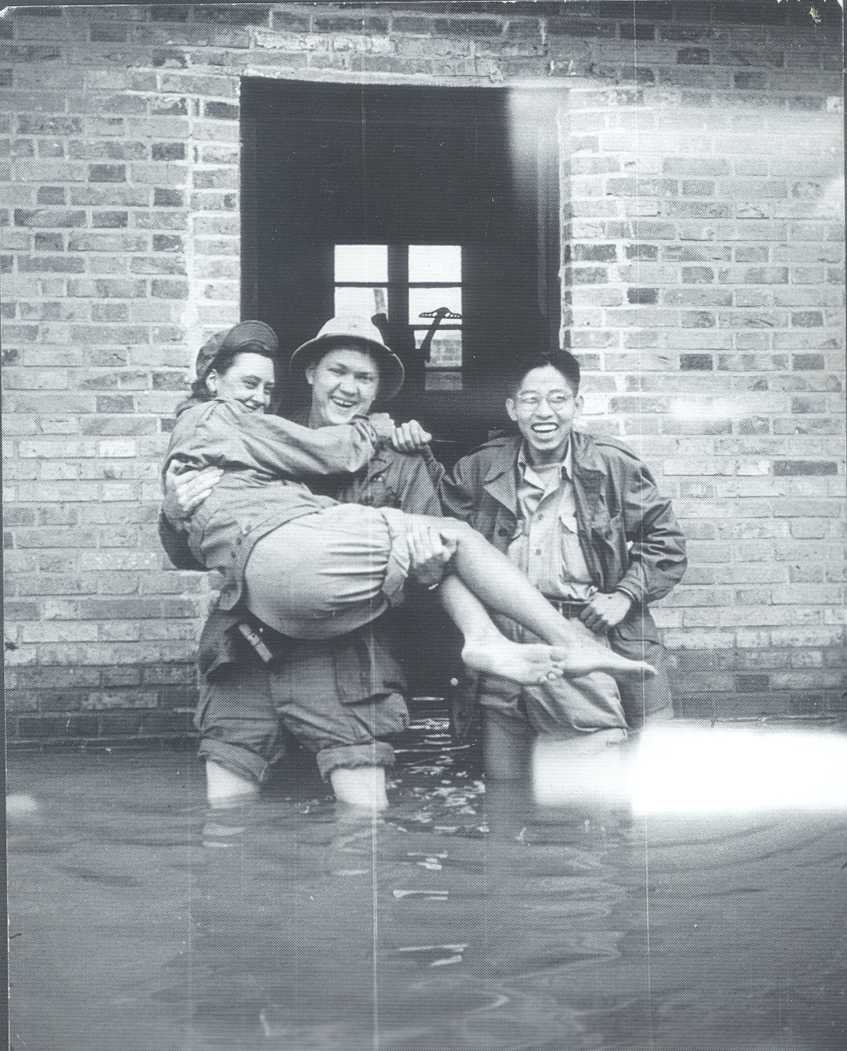

Betty in Ceylon (Sri Lanka). 1945.

The Woman who Chronicled The Sisterhood of Spies: Elizabeth “Betty” McIntosh

“I always wanted to be a journalist,” recalled Betty. “And, in a way, I always was a journalist.”

The daughter of two reporters, Elizabeth Peet (McIntosh) was born in Washington, D.C. on March 1, 1915. The Peet family moved to Honolulu, Hawaii in 1925, and young Betty became fascinated with Japanese culture and language. She attended the University of Washington and earned a degree in journalism. When she returned to Hawaii, her father got her a job with the Honolulu Advertiser, where Betty started off writing for the sports column, eventually moving up to feature stories. She also continued studying Japanese, hoping to get a reporter job with AP or UPI. Then, Pearl Harbor happened.

Betty witnessed Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, first hand and wrote about the aftermath for the Scripps Howard News Service. A couple of years later, Betty was recruited by the OSS for her fluent Japanese language skills. She became one of the few women assigned to the Morale Operations Branch (MOB), where she created disinformation reports, postcards, and radio messages designed to undermine the morale of Japanese troops. Her work with the MOB would take her overseas to India, Burma and China.

In 1945, on a bumpy night flight to Ceylon (present day Sri Lanka), Betty found herself on a plane with fellow OSS officer Julia McWilliams. As the plane flew through a storm and rocked back and forth, Betty thought this was it! She didn’t think she was going to survive the flight. She nervously looked over at McWilliams, who calmly continued reading her book and eating an apple as if nothing was wrong. Seeing McWilliams’ composure put Betty somewhat at ease.

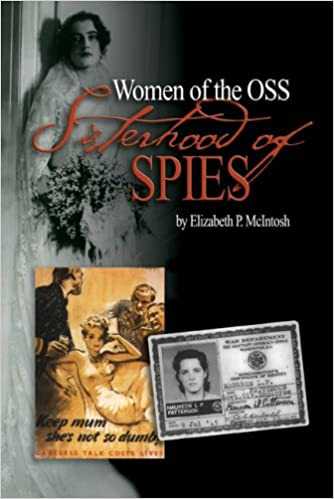

The cover of Betty’s book. Published in 1998.

Suffice to say, Betty and McWilliams survived that flight–and whatever happened to Julia McWilliams, you ask? Well, she married fellow OSS officer Paul Child. After the war, Paul Child joined the Foreign Service and the Childs were posted in Paris, France, where Julia Child began to study French cooking. The rest, as they say, is (culinary) history.

After the war, Betty worked various jobs with the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the State Department and Voice of America. She fell back to her first love, writing, and chronicled her OSS exploits in her memoir, “Undercover Girl,” published in 1947. In 1958, she joined the CIA, where she worked until her retirement in 1973.

In the 1990s, Betty wanted to write a history of the brave women who played an important part in OSS, and went about contacting female OSS veterans for interviews. Betty interviewed over 140 former officers, including Cordelia Hood, Gertrude Legendre, Julia Child and Maria Gulovich among others (Betty did not know Doris Bohrer at the time). In 1998, “The Women of the OSS: Sisterhood of Spies” was published and the world finally got to read about the amazing stories of these courageous, extraordinary women who stepped up—and broke barriers—to answer the call of duty.

It might be hard to believe, but Betty McIntosh and Doris Bohrer’s paths never crossed during their careers as young female OSS officers. It wouldn’t be until decades later, in the late 2000’s to be exact, when widows Betty and Doris found themselves living in the same retirement community in Northern Virginia.

One day, as a group of retirees were sitting around the lunch room reminiscing about World War II, that Betty and Doris discovered that they had both served in the OSS around the same time—and even worked in the same building in Washington. Given their unique professional connection, the two women became fast friends.

Director Brennan invited Betty McIntosh to HQS to celebrate her 100th birthday in 2015. Here she is with a specially-prepared cake.

They looked out for each other, and spent time sharing their OSS stories. Unsurprisingly, Betty and Doris formed a bond of friendship that lasted until the end of their days.

In a Washington Post interview published in 2011, the two women talked about their inseparable friendship: “After the war, people weren’t interested in hearing any war stories. First off they probably didn’t believe us.” But oh, the stories they must have told!

On March 3, 2015, Director John Brennan invited Betty McIntosh to Langley to celebrate an important milestone—her 100th birthday. Sadly, Betty passed away two months later. Her dear friend—and fellow OSS “sister” Doris Bohrer was deeply saddened by Betty’s death. Doris passed away a year later, in August of 2016.

Two remarkable women, two remarkable legacies.

General Donovan (center left) stands alongside some of his glorious amateurs.

OSS Comes to an End

“We have come to the end of an unusual experiment. This experiment was to determine whether a group of Americans constituting a cross-section of racial origins, of abilities, temperaments and talents, could risk an encounter with the long-established and well-trained enemy organizations.”

~ General William “Wild Bill” Donovan, September 1945

After the end of WWII, President Truman signed Executive Order 9621, dissolving the OSS in the fall of 1945. It would be another two years until the CIA was created, on September 18, 1947.

Though the OSS was ultimately disbanded, these amazing women proved that General Donovan’s unusual experiment was a success, and they paved the way forward for the women of CIA today.