As CIA marks our 75th anniversary, the Agency recently had the privilege of hosting Sherman Wetmore, a lead engineer on the Glomar Explorer. Glomar was the ship that supported a covert CIA operation to recover a Soviet submarine that sank to the floor of the Pacific Ocean in 1968. CIA recognized the tremendous intelligence potential and embarked on a six-year mission, code-named Project AZORIAN, to recover the vessel and gain insights into Soviet strategic capabilities. AZORIAN, set against the backdrop of the Cold War, was a critical endeavor that married the ingenuity of the CIA with the expertise of private sector engineers.

Sherman Wetmore looking at an oil painting of the Glomar Explorer raising the Soviet submarine. The painting is displayed in one of CIA’s corridors and has a placard that reads: “We Are Only Limited By Our Imagination” (not shown)

During his visit, Wetmore, who worked as a mechanical engineer for Global Marine from 1961 until he retired in 1996, sat down with CIA historians and recounted his memories of the AZORIAN mission. Back then, he worked with a team of roughly ten engineers, all working 12-hour shifts under constant threat of Soviet discovery and mechanical mishaps. Talking through the technical parameters and challenges that he and his crew faced, Wetmore referred to the mechanical claw designed to grab onto and lift the submarine as “Clementine,” the nickname that had stuck with the crew.

Project AZORIAN was among America’s greatest Cold War intelligence coups, but the mission was incomplete. In 1974, as Glomar operators were hoisting the submarine up from its slumber three-miles below the water’s surface, the submarine came apart, and a section plunged back down. “Why the claw broke has continued to haunt me,” he shared.

Sherman Wetmore with CIA Museum Deputy Director.

The mechanical failure haunts him because, in a strange and unfortunate series of events, the mission was never fully completed. Just before Glomar set off to collect the remaining portion of the submarine left behind on the ocean floor, the cover story for the daring operation was publicly exposed. National headlines disclosed that billionaire Howard Hughes was not actually undertaking a commercial deep-sea mining expedition, rather the CIA was engaged in an operation to salvage a Soviet submarine. With that, Project AZORIAN came to an end.

After all of these years, the Agency welcomed Wetmore for his first visit to the CIA, where he became acquainted with a new generation of CIA counterparts and relived the mission for posterity.

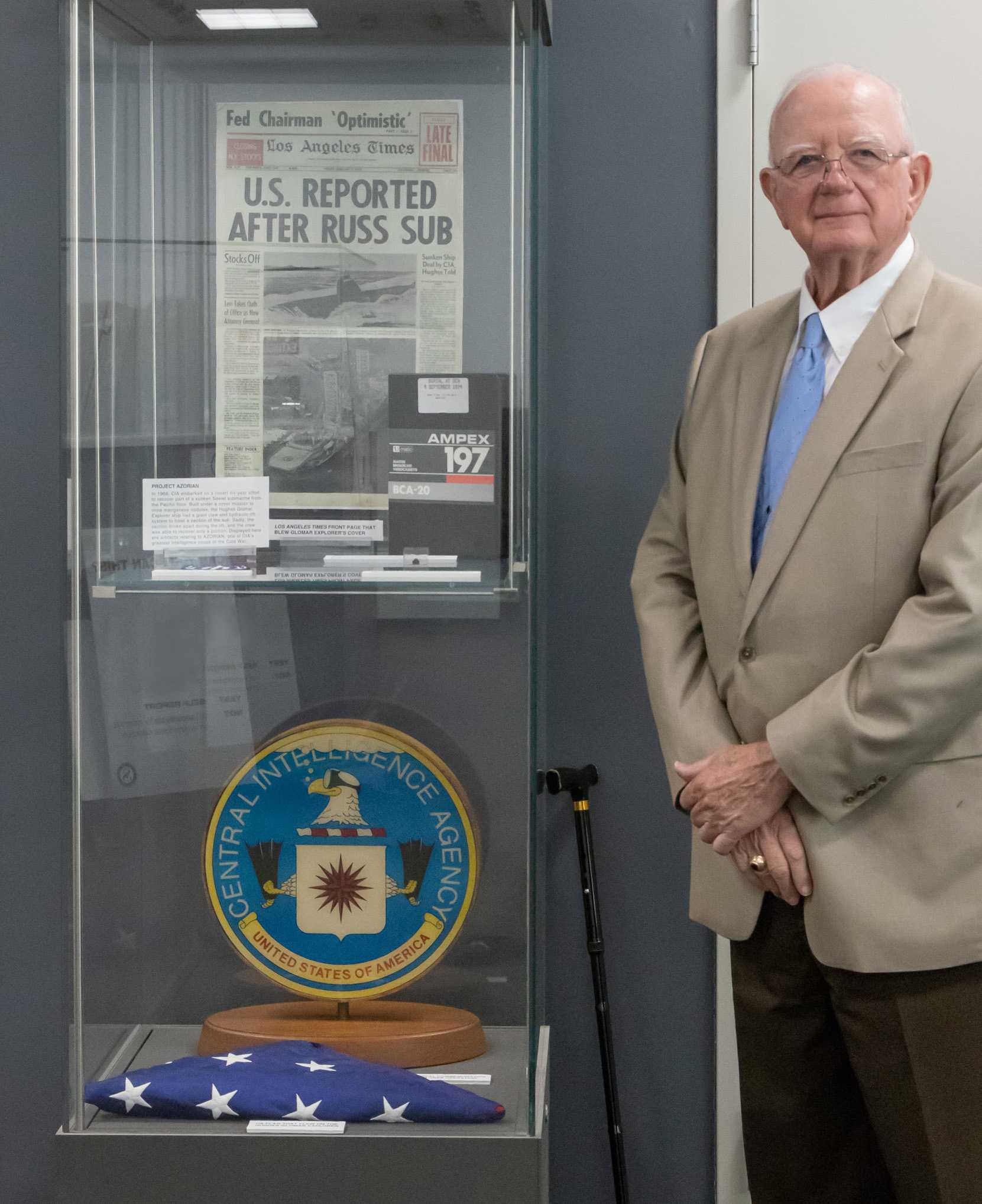

CIA officers took Wetmore and a few of his family members on a tour of the Museum at our Headquarters in Langley, Virginia, stopping at one exhibit in particular. There, inside a glass case, featured a patch worn by Glomar Explorer crewmembers, the seal that CIA had designed in the 1970s to commemorate Project AZORIAN, the U.S. flag that flew on the Glomar Explorer, and a copy of a newspaper with the front-page headline “U.S. Reported After Russ Sub” dated February 7th, 1975. As Wetmore stood poring over the artifacts, his family was curious about his reaction when he learned that the media had blown the cover on his secret mission. “Well, I was mad!” he answered, “But it was inevitable.”

Collection of Project AZORIAN artifacts on display.

Wetmore also underscored the collegiality among the various contractors and Agency officers involved in Project AZORIAN in that everyone engaged in a mission to defend the nation from a foreign threat. “The patriotism was unbelievable and there was a lot of pride in keeping things secret. There was a lot of respect on both sides; CIA admired the engineers’ work ethic, and contractors respected the security preparations and thoroughness of the CIA.”