Elizabeth “Betty” McIntosh lived a storied, adventurous life. During WWII, she was one of the few women hired into the OSS Morale Operations (MO) branch, charged with creating rumors that our foreign adversaries would believe. In other words, so-called “black propaganda.”

Betty helped create false news reports, postcards, documents, and radio messages designed to spread disinformation to undermine Japanese troop morale. In one truly inexplicable incident, she created a script for a popular Chinese fortune teller to read on a radio station secretly run by the Allies that predicted “something awful” was about to happen in Japan. Her team had no inkling something bad was actually going to happen, but later that day, the US dropped the atom bomb on Hiroshima.

When OSS was disbanded, Betty tried on a few different careers but eventually was convinced to return to a life in intelligence at CIA. She worked for the Agency until her retirement in 1973. As the author of several books, including “Sisterhood of Spies,” Betty made sure that the stories of the women of OSS and their daring adventures would never be forgotten.

Perhaps it’s fitting, then, that Women’s History Month begins each year on March 1st, the birthday of “Spy Girl” Betty McIntosh.

Recruited by OSS:

A Washington, D.C. native, Betty was born on March 1, 1915. After graduating from the University of Washington, School of Journalism, Betty moved to Hawaii and worked for several news outlets, including the Honolulu Advertiser, Star Bulletin, and San Francisco Chronicle. Betty was working as a reporter in Hawaii when Japanese forces attacked Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. Betty covered the event first-hand and soon left Hawaii to work in the Scripps Howard bureau in Washington, D.C.

During talks with CIA Historians on May 2, 1997 and June 24, 2002, Betty explained how she came to work for OSS. In 1943, Betty’s supervisors wanted her to write a story on a man named Atherton Richards who had been the head of a firm in Honolulu working on the mechanization of sugar cane harvesting. Richards also happened to be one of the top officials serving under General William J. “Wild Bill” Donovan, the then-chief of the OSS.

“He was a friend of my father’s,” Betty recalled. “It was very difficult to get in to see him, but I finally managed to. After our interview he said, ‘Wouldn’t you like to get into something interesting like…’ you know, he didn’t say ‘spying’ but he just said, ‘more interesting maybe than the work you’re doing,’ although I was covering Eleanor Roosevelt at the White House and that wasn’t too bad. I said I would be interested if it meant going overseas. He said, ‘I can promise you that.’ So that’s how I joined OSS.”

Fluent in Japanese, Betty was recruited in 1943 to join the OSS, CIA’s predecessor and the nation’s first intelligence agency.

Betty describes her first visit to the OSS as “very strange.” When she arrived on duty, they didn’t tell her anything about what her job would be. “They fingerprinted me and told me not to speak about anything, although I didn’t know anything anyway. Security moved in as soon as you joined OSS.”

Betty was one of the few women assigned to OSS Morale Operations (MO). “Eventually I was introduced to the MO group in Washington and then I was informed what my duties were.”

The MO branch was in the business of creating rumors that our foreign adversaries would believe. In other words, black propaganda. Betty worked for the Far East division, while the other MO branch serviced Europe. “They taught us how to utilize material tailored for specific targets in the Far East. We had to learn to disseminate the material, a mix of truth and fantasy; we were taught how to get rumors started, for example.” It was at this point that Betty learned basic tradecraft, the same time-honored skills taught to intelligence officers today, skills that served her well in a post-war career at the CIA.

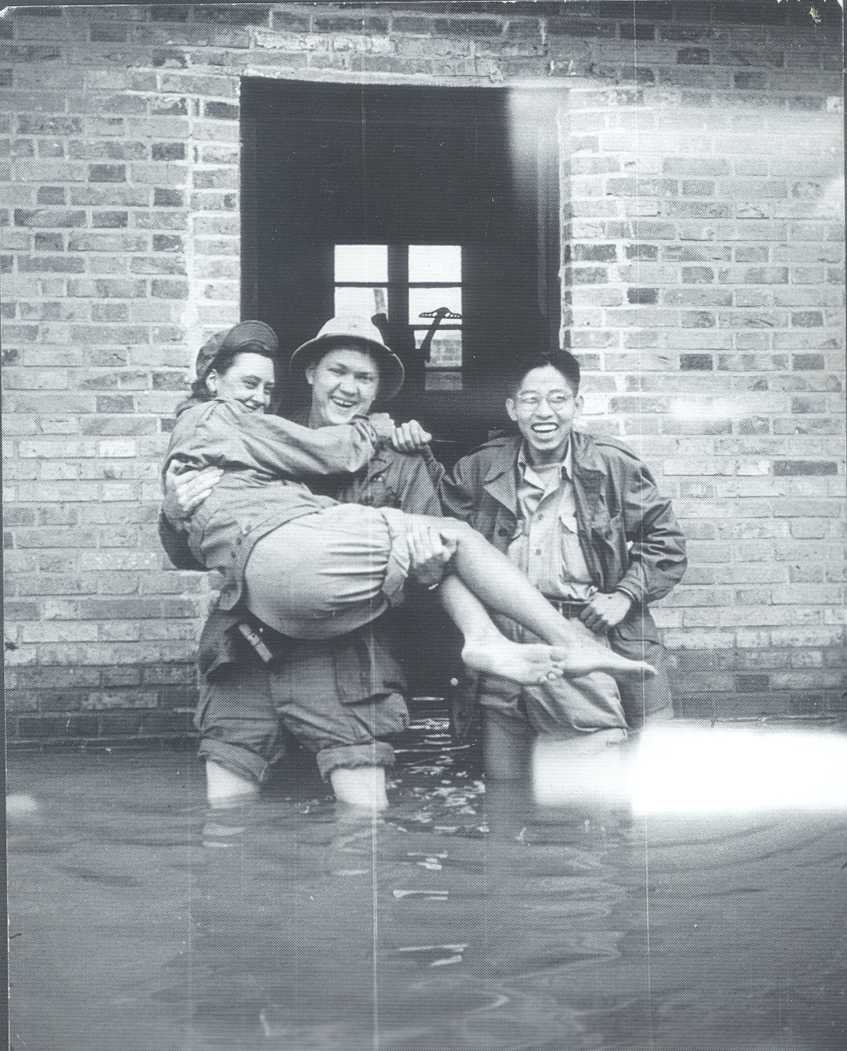

“The group was mostly made up of newspaper men, radio people, artists, cartoonists, and some writers,” said Betty. “Mainly it was the media. That was what the OSS wanted for a quick production start.” Betty’s team included several artists from China, as well as captured Japanese soldiers who were artists in civilian life and willingly offered their talents to the Allied cause.

Hiring a group of artists and writers to create black propaganda campaigns came with several challenges. “They didn’t react to authority very well,” according to Betty. “I remember the artists and writers lounging around in the office, and when an officer entered the room they would just say ‘Hi fellow’ or just ‘Hi.’ They wouldn’t say ‘Colonel,’ ‘Sir,’ or anything like that. And they never learned to salute. Their uniforms were awfully sloppy too.”

World War II Exploits:

Betty’s first assignment was in the summer of 1943. After completing her OSS training, she was sent to India. Betty helped produce false news reports, radio messages, and other propaganda designed to spread disinformation that would undermine Japanese troops, who were already demoralized and retreating from their defeat by Allied forces on the Imphal Plain. This included efforts to distribute forged Japanese government orders to Japanese troops in Burma.

“The Japanese government told their soldiers that if they surrendered they would lose their birth right and would not be able to go back to Japan,” explained Betty. “So consequently very few Japanese surrendered. They cost us a great deal because they fought to the very end and many of our people, too, were killed. So the idea was to try to get them to give up without feeling that they had lost their identity.”

In order to undermine the notion that surrender was unacceptable, Betty and her team crafted a forged order permitting Japanese troops to surrender under certain conditions. This was a believable scenario because there had recently been a leadership change in the Japanese government, which led to a window of uncertainty.

Betty and her team enlisted a Burmese OSS agent to kill a Japanese courier en route through the jungle and insert the forged order into his knapsack. This “wily little killer” then reported to the Japanese on the whereabouts of their dead courier. Predictably, and according to plan, the Japanese retrieved their man with his mailbag and found the order that they concluded was authentic.

Having accomplished a great deal in India, Betty boarded a flight in Dum-Dum Airport, Calcutta, and accompanied by her dear friend, Julia McWilliams (Child), flew the infamous “Hump” through the Himalayas destined for Kunming, China, behind enemy lines. Being a newspaper journalist, Betty had never worked in broadcast radio. Her new challenge was to create scripts for a “black radio station” into China, and ultimately the home islands of Japan. Betty explained one of the last campaigns the OSS conducted:

The OSS had somebody that they called the seer there, he was a fortune teller. Evidently, the Chinese loved to listen to him because he would predict things that would happen according to the stars. I remember going in to the radio room, very late in the war, and one of my supervisors, Gordon, was saying, “We’ve got to get something on the program that will just shake the Chinese and the Japanese,” and I said, “Well, let’s have a big earthquake happen in Japan.” Gordon objected, “They’re always having earthquakes.” I said, “Then let’s have a tidal wave to go with it.” “No, that’s nothing either,” he said. “I’ll think of something,” I told him.

The seer soon went on the air and predicted that “something terrible is going to happen to Japan. We have checked the stars and there is something we can’t even mention because it is so dreadful and it is going to eradicate one whole area of Japan.” That day, we dropped the atom bomb on Hiroshima.

Betty said it was pure coincidence that the bomb was dropped after the radio broadcast went out. Colonel Richard “Dick” Heppner, who would later become Betty’s husband, came up to her afterwards and asked, “How in the world did you find about this [the bomb]?” because it was top secret.

“We just made it up, you know,” said Betty, “but that’s the sort of thing we did.”

OSS Disbands:

At war’s end, Betty returned to the US and, as the OSS had been disbanded, she found work with Glamour magazine in New York City. After her wartime experience creating black propaganda, she found writing for a fashion magazine underwhelming. More suited to her talents was a position which opened up with Voice of America, an organization, not surprisingly, that found early support from none other than General William “Wild Bill” Donovan himself. In this capacity, Betty was able to put her OSS skills to work once again in service to her country during the Cold War.

She married Colonel Heppner in May 1946 and they moved back to DC, where Betty worked on assignments for the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the State Department, and the United Nations. In weekly consultations with her former boss, General Donovan, she wrote a memoir, Undercover Girl, published in 1947 – a humorous and yet poignant account of her experiences in China, Burma and India during the war.

She began a new chapter in her life with the publication of two vibrant children’s books: Inki in 1957 and Palaces Under the Sea, 1959. After her beloved husband, Richard Heppner died, Betty’s friends, now working for the CIA, convinced her to go talk to then-CIA Director Allen Dulles about possible employment.

“I just went over and asked Allen Dulles if I could have a job,” recalled Betty. “He said he was designing his new place [CIA Headquarters Building]. He said, ‘It’s going to be just like a college campus, nothing like that stone-wall place that my brother [Secretary of State John Foster] lives in.'”

Life at CIA:

Betty was among several OSS women who joined the CIA after the OSS was disbanded. “I think that OSS, as the forerunner for CIA, laid the groundwork for what is now CIA,” said Betty. “Without the OSS I don’t think they could have created such an agency.”

Betty found the culture at the CIA a little different than what she had experienced at the OSS. “There was a little bit of bureaucracy, which had set in like rigor mortis up above us, and some people were sort of… they didn’t have imaginations… they didn’t want to do things like we did in OSS.”

Some things were the same. Case officers at the CIA were predominantly male. Having worked in male-dominated industries her entire life, Betty had always gotten along well with her male colleagues, who mostly treated her as an equal. “I guess maybe I developed something that helped me. An attitude, maybe. Especially in OSS, I felt I was just absolutely an equal with anybody in the office.”

Betty carried this attitude into her CIA career. Not all OSS women who joined the Agency managed to do this. Betty recalled that women who had proved their competence during the war were, “often just sort of considered as secretaries, and, therefore, you know, ‘take this paper and go.’ I didn’t like that attitude in a lot of the men, the way they treated [them], but what can you do?”

Betty’s experience in the OSS served her well. “I learned to be covert about things and not to shoot my mouth off. The stuff I was doing for the Agency was similar to what I had been doing in OSS, but I guess I can’t talk much about it. I had a signed pledge not to reveal my work.”

Living History:

Betty served overseas on several assignments. While serving in Asia, she met a dashing fighter pilot, Fred McIntosh, and married him in May of 1962. After 40 years of service to her country in the field of intelligence, she retired in 1973.

Betty has endeavored to maintain contact with her OSS colleagues over the years. “There’s not many of us left now,” she noted. Her 1998 book, Sisterhood of Spies: The Women of the OSS, is an homage to the brave women who served in the OSS as part of “Donovan’s Dreamers,” those “glorious amateurs” who laid the foundation for the greatest intelligence organization in history.

Betty returned to CIA Headquarters on March 1, 2015, to celebrate her 100th birthday, delighting and inspiring fresh-faced young officers with stories of her decades of adventures.

“I’m glad I was in OSS,” Betty said when asked to sum up her career. “It was a wonderful experience and I cherish it as the most exciting part of my life.”

Betty McIntosh died a few months later, on June 8, 2015. She was 100 years old.