Introduction

Background

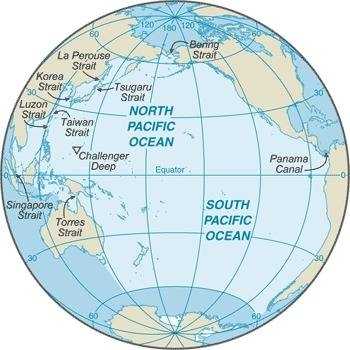

The Pacific Ocean is the largest of the world's five ocean basins (followed by the Atlantic Ocean, Indian Ocean, Southern Ocean, and Arctic Ocean). Strategically important access waterways include the La Perouse, Tsugaru, Tsushima, Taiwan, Singapore, and Torres Straits. The International Hydrographic Organization decision in 2000 to delimit a fifth world ocean basin, the Southern Ocean, removed the portion of the Pacific Ocean south of 60 degrees south. For convenience and because of its immense size, the Pacific Ocean is often divided at the Equator and designated as the North Pacific Ocean and the South Pacific Ocean.

Visit the Definitions and Notes page to view a description of each topic.

Geography

Location

body of water between the Southern Ocean, Asia, Australia, and the Western Hemisphere

Geographic coordinates

0 00 N, 160 00 W

Area

total : 168.723 million sq km

note: includes Arafura Sea, Bali Sea, Banda Sea, Bering Sea, Bering Strait, Celebes Sea, Coral Sea, East China Sea, Flores Sea, Gulf of Alaska, Gulf of Thailand, Gulf of Tonkin, Java Sea, Philippine Sea, Sea of Japan, Sea of Okhotsk, Solomon Sea, South China Sea, Sulu Sea, Tasman Sea, and other tributary water bodies

Area - comparative

about 15 times the size of the US; covers about 28% of the global surface; almost equal to the total land area of the world

Coastline

135,663 km

Climate

planetary air pressure systems and resultant wind patterns exhibit remarkable uniformity in the south and east; trade winds and westerly winds are well-developed patterns, modified by seasonal fluctuations; tropical cyclones (hurricanes) may form south of Mexico from June to October and affect Mexico and Central America; continental influences cause climatic uniformity to be much less pronounced in the eastern and western regions at the same latitude in the North Pacific Ocean; the western Pacific is monsoonal - a rainy season occurs during the summer months, when moisture-laden winds blow from the ocean over the land, and a dry season during the winter months, when dry winds blow from the Asian landmass back to the ocean; tropical cyclones (typhoons) may strike southeast and east Asia from May to December

Ocean volume

ocean volume: 669.88 million cu km

percent of World Ocean total volume: 50.1%

Major ocean currents

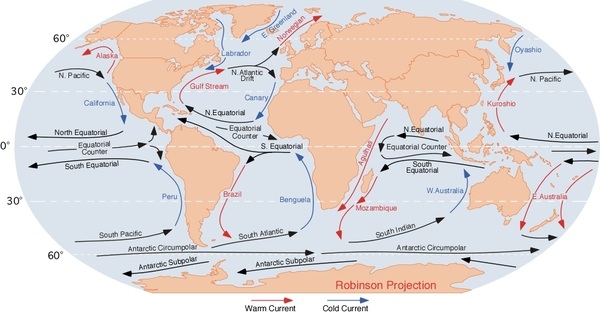

the clockwise North Pacific Gyre formed by the warm northward flowing Kuroshio Current in the west, the eastward flowing North Pacific Current in the north, the southward flowing cold California Current in the east, and the westward flowing North Equatorial Current in the south; the counterclockwise South Pacific Gyre composed of the southward flowing warm East Australian Current in the west, the eastward flowing South Pacific Current in the south, the northward flowing cold Peru (Humbolt) Current in the east, and the westward flowing South Equatorial Current in the north

Bathymetry

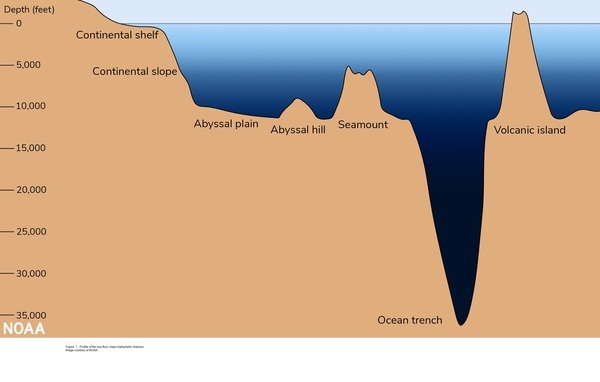

continental shelf: The continental shelf (see Figure 1), a rather flat area of the sea floor adjacent to the coast that gradually slopes down from the shore to water depths of about 200 m (660 ft). Dimensions can vary: they may be narrow or nearly nonexistent in some places or extend for hundreds of miles in others. The waters along the continental shelf are usually productive in both plant and animal life, from sunlight and nutrients from ocean upwelling and terrestrial runoff. The following are examples of features found on the continental shelf of the Pacific Ocean:

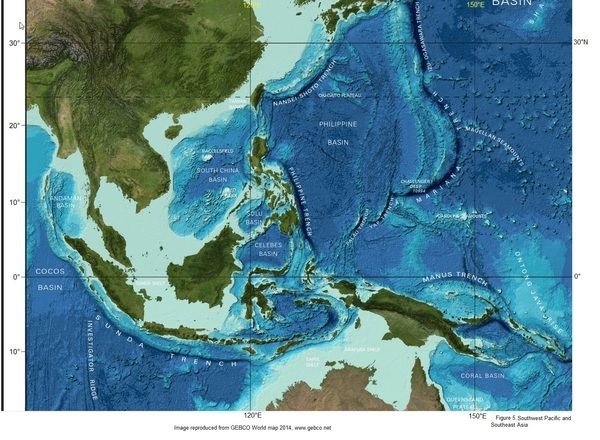

Arafura Shelf (Figure 5)

Sahul Shelf (Figure 5)

Sunda Shelf (Figure 5)

Taiwan Banks (Figure 5)

continental slope: The continental slope (see Figure 1) is where the ocean bottom drops off more rapidly until it meets the deep-sea floor (abyssal plain) at about 3,200 m (10,500 ft) water depth. The deep waters of the continental slope are characterized by cold temperatures, low light conditions, and very high pressures. Sunlight does not penetrate to these depths, having been absorbed or reflected in the water above. The continental slope can be indented by submarine canyons, often associated with the outflow of major rivers. Another feature of the continental slope is alluvial fans, or cones of sediments, that major rivers carry downstream to the ocean and deposit down the slope. The following are examples of features found on the continental slope of the Pacific Ocean:

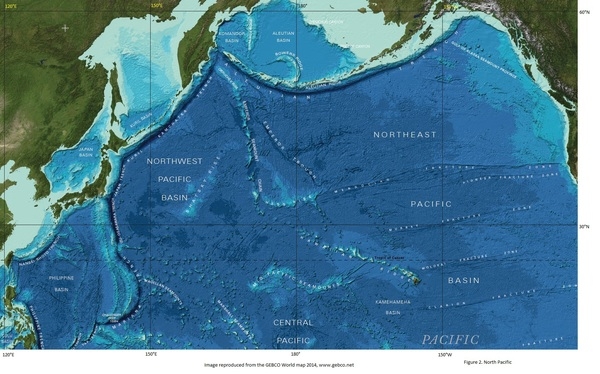

Pribilof Canyon (Figure 2)

Zhemchug Canyon (Figure 2); note - deepest submarine canyon

abyssal plains: The abyssal plains (see Figure 1), at depths of over 3,000 m (10,000 ft) and covering 70% of the ocean floor, are the largest habitat on earth. Sunlight does not penetrate to the sea floor, making these deep, dark ecosystems less productive than those along the continental shelf. Despite their name, these “plains” are not uniformly flat; they are interrupted by features like hills, valleys, and seamounts. The following are examples of features found on the abyssal plains of the Pacific Ocean:

Aleutian Basin (Figure 2)

Central Pacific Basin (Figure 2)

Northeast Pacific Basin (Figure 2)

Northwest Pacific Basin (Figure 2)

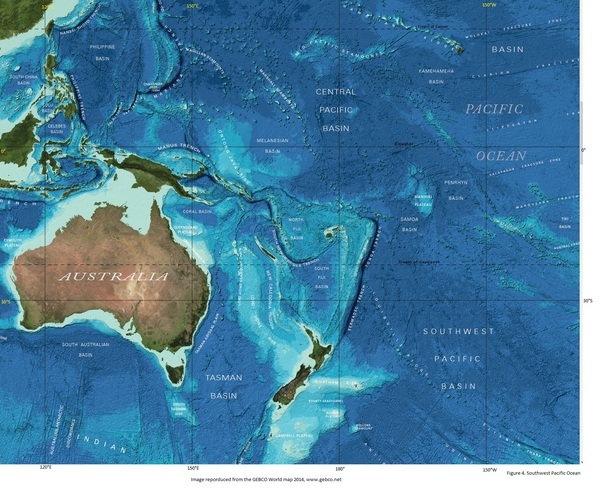

Philippine Basin (Figure 4)

Southwest Pacific Basin (Figure 4)

Tasman Basin (Figure 4)

mid-ocean ridge: The mid-ocean ridge (see Figure 1), rising up from the abyssal plain, is an underwater mountain range over 64,000 km (40,000 mi) long, reaching an average depth of 2,400 m (8,000 ft). Mid-ocean ridges form at divergent plate boundaries where two tectonic plates are moving apart and magma pushing up from the mantle creates new crust. Tracing their way around the global ocean, this system of underwater volcanoes forms the longest mountain range on earth. Fracture zones are linear transform faults that develop perpendicular to the line of the mid-ocean ridge, which can offset the ridge line and divide it into segments. The following are examples of mid-ocean ridges found on the floor of the Pacific Ocean:

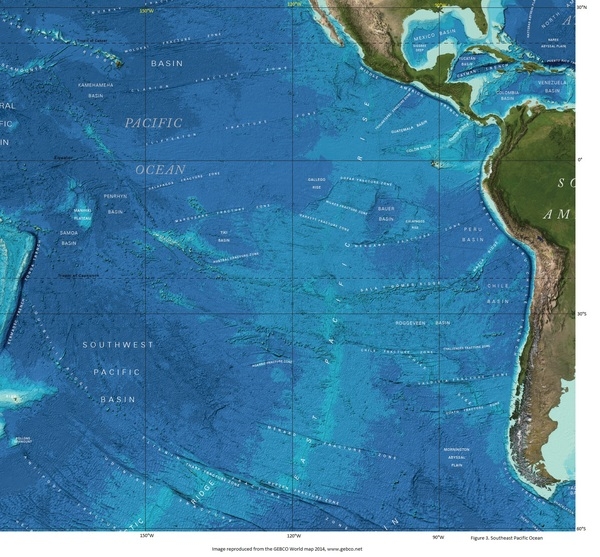

East Pacific Rise (Figure 3)

Pacific-Antarctic Ridge (Figure 3)

undersea terrain features: The Abyssal Plain is commonly interrupted by a variety of commonly named undersea terrain features including seamounts, guyots, ridges, and plateaus.

Seamounts (see Figure 1) are submarine mountains at least 1,000 m (3,300 ft) high formed from individual volcanoes on the ocean floor. They are distinct from the plate-boundary volcanic system of the mid-ocean ridges, because seamounts tend to be circular or conical. A circular-collapse caldera is often centered at the summit, evidence of a magma chamber within the volcano. "Hot spots" in the deep mantle often feed long chains of seamounts. These hot spots are associated with stationary plumes of molten rock rising from deep within the Earth's mantle. The hot-spot plumes melt through the overlying tectonic plate as it moves and supplies magma to the active volcanic island at the end of the chain of volcanic islands and seamounts.

Flat topped seamounts are known as guyots.

An undersea ridge is an elongated elevation of varying complexity and size, generally having steep sides.

An undersea plateau is a large, relatively flat elevation that is higher than the surrounding relief with one or more relatively steep sides. Although submerged, these features can reach close to sea level.

The following are examples of undersea terrain features found on the floor of the Pacific Ocean:

Caroline Seamounts (Figure 5)

East Mariana Ridge (Figure 4)

Emperor Seamount Chain (Figure 2)

Hawaiian Ridge (Figure 2)

Lord Howe Seamount Chain (Figure 4)

Louisville Ridge (Figure 4)

Kapingamarangi (Ontong-Java) Rise (Figure 5); note - largest submarine plateau

Macclesfield Bank (Figure 5)

Marshall Seamounts (Figure 2)

Magellan Seamounts (Figure 2)

Mid-Pacific Seamounts (Figure 2)

Reed Tablemount (Figure 5)

Shatsky Rise (Figure 2); note - third largest submarine plateau

Tonga-Kermadec Ridge (Figure 4)

ocean trenches: Ocean trenches (see Figure 1) are the deepest parts of the ocean floor and are created by the process of subduction. Trenches form along convergent boundaries where tectonic plates are moving toward each other, and one plate sinks (is subducted) under another. The location where the sinking of a plate occurs is called a subduction zone. Subduction can occur when oceanic crust collides with and sinks under (subducts) continental crust resulting in volcanic, seismic, and mountain-building processes. Subduction can also occur in the convergence of two oceanic plates, where one will sink under the other and in the process create a deep ocean trench.

Subduction processes in oceanic-to-oceanic plate convergence also result in the formation of volcanoes. Over millions of years, the erupted lava and volcanic debris pile up on the ocean floor until a submarine volcano rises above sea level to form a volcanic island. Such volcanoes are typically strung out in curved chains called island arcs.

The following are examples of ocean trenches found on the floor of the Pacific Ocean:

Aleutian Trench (Figure 2)

Chile Trench (Figure 3)

Izu-Ogasawara Trench (Figure 2)

Japan Trench (Figure 2)

Kermadec Trench (Figure 3, 4)

Kuril-Kamchatka Trench (Figure 2)

Manus Trench (Figure 4)

Mariana Trench (Figure 2, 4); note - deepest ocean trench

Middle America Trench (Figure 3)

Nansei-Shoto Trench (Figure 5)

Palau Trench (Figure 2, 4)

Philippine Trench (Figure 4)

Peru-Chile Trench (Figure 3)

South New Hebrides Trench (Figure 4)

Tonga Trench (Figure 3, 4)

Yap Trench (Figure 2, 4)

atolls: Atolls are the remains of dormant volcanic islands. In warm tropical oceans, coral colonies establish themselves on the margins of the island. Then, over time, the high elevation of the island collapses and erodes away to sea level, leaving behind an outline of the island in the form of the fringing coral reef. The resulting low island is typified by the coral reef that surrounds a low elevation of sand and coral, with an interior shallow lagoon. Often the remaining dry land is broken into a ring of islets, and some lagoons can be hundreds of square kilometers.

Guyots are submerged atoll structures, which explains why they are flat-topped seamounts.

The following are examples of atolls found in the Pacific Ocean, and because most of these are also countries or territories, they have entries in The World Factbook with additional information:

Federated States of Micronesia

French Polynesia

Kiribati

Marshall Islands

Midway Island

Tonga

Tuvalu

Vanuatu

Wake Island

Elevation

highest point: sea level

lowest point: Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench -10,924 m; note - the Pacific Ocean is the deepest ocean basin

mean depth: -4,080 m

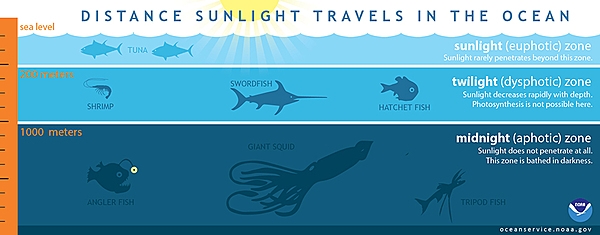

ocean zones: Composed of water and in a fluid state, the ocean is delimited differently than the solid continents. It is divided into three zones based on depth and light level. Sunlight entering the water may travel about 1,000 m into the oceans under the right conditions, but there is rarely any significant light beyond 200 m.

The upper 200 m (656 ft) of the ocean is called the euphotic, or "sunlight," zone. This zone contains the vast majority of commercial fisheries and is home to many protected marine mammals and sea turtles. Only a small amount of light penetrates beyond this depth.

The zone between 200 m (656 ft) and 1,000 m (3,280 ft) is usually referred to as the "twilight" zone, but is officially the dysphotic zone. In this zone, the intensity of light rapidly dissipates as depth increases. Such a minuscule amount of light penetrates beyond a depth of 200 m that photosynthesis is no longer possible.

The aphotic, or "midnight," zone exists in depths below 1,000 m (3,280 ft). Sunlight does not penetrate to these depths, and the zone is bathed in darkness.

Natural resources

oil and gas fields, polymetallic nodules, sand and gravel aggregates, placer deposits, fish

Natural hazards

surrounded by a zone of violent volcanic and earthquake activity sometimes referred to as the "Pacific Ring of Fire"; up to 90% of the world's earthquakes and some 75% of the world's volcanoes occur within the Ring of Fire; 80% of tsunamis, caused by volcanic or seismic events, occur within the "Pacific Ring of Fire"; subject to tropical cyclones (typhoons) in southeast and east Asia from May to December (most frequent from July to October); tropical cyclones (hurricanes) may form south of Mexico and strike Central America and Mexico from June to October (most common in August and September); cyclical El Niño/La Niña phenomenon occurs in the equatorial Pacific, influencing weather in the Western Hemisphere and the western Pacific; ships subject to superstructure icing in extreme north from October to May; persistent fog in the northern Pacific can be a maritime hazard from June to December

Geography - note

the major chokepoints are the Bering Strait, Panama Canal, Luzon Strait, and the Singapore Strait; the Equator divides the Pacific Ocean into the North Pacific Ocean and the South Pacific Ocean; dotted with low coral islands and rugged volcanic islands in the southwestern Pacific Ocean; much of the Pacific Ocean's rim lies along the Ring of Fire, a belt of active volcanoes and earthquake epicenters that accounts for up to 90% of the world's earthquakes and some 75% of the world's volcanoes; the Pacific Ocean is the deepest ocean basin averaging 4,000 m in depth

Environment

Environment - current issues

pollution from land- and sea-based sources (such as sewage, nutrient runoff from agriculture, plastic pollution, and toxic waste); habitat destruction; over-fishing; climate change leading to sea level rise, ocean acidification, and warming; endangered marine species include the dugong, sea lion, sea otter, seals, turtles, and whales; oil pollution in Philippine Sea and South China Sea

Climate

planetary air pressure systems and resultant wind patterns exhibit remarkable uniformity in the south and east; trade winds and westerly winds are well-developed patterns, modified by seasonal fluctuations; tropical cyclones (hurricanes) may form south of Mexico from June to October and affect Mexico and Central America; continental influences cause climatic uniformity to be much less pronounced in the eastern and western regions at the same latitude in the North Pacific Ocean; the western Pacific is monsoonal - a rainy season occurs during the summer months, when moisture-laden winds blow from the ocean over the land, and a dry season during the winter months, when dry winds blow from the Asian landmass back to the ocean; tropical cyclones (typhoons) may strike southeast and east Asia from May to December

Marine fisheries

the Pacific Ocean fisheries are the most important in the world, accounting for 58.1%, or 45,800,000 mt, of the global marine capture in 2020; of the six regions delineated by the Food and Agriculture Organization in the Pacific Ocean, the following are the most important:

Northwest Pacific region (Region 61) is the world’s most important fishery, producing 24.3% of the global catch or 19,150,000 mt in 2020; it encompasses the waters north of 20º north latitude and west of 175º west longitude, with the major producers including China (29,080726 mt), Japan (3,417,871 mt), South Korea (1,403,892 mt), and Taiwan (487,739 mt); the principal catches include Alaska pollock, Japanese anchovy, chub mackerel, and scads

Western Central Pacific region (Region 71) is the world’s second most important fishing region producing 16.8%, or 13,260,000 mt, of the global catch in 2020; tuna is the most important species in this region; the region includes the waters between 20º North and 25º South latitude and west of 175º West longitude with the major producers including Indonesia (6,907,932 mt), Vietnam (4,571,497 mt), Philippines (2,416,879 mt), Thailand (1,509,574 mt), and Malaysia (692,553 mt); the principal catches include skipjack and yellowfin tuna, sardinellas, and cephalopods

Southeast Pacific region (Region 87) is the third largest fishery in the world, producing 10.7%, or 8,400,000 mt, of the global catch in 2020; this region includes the nutrient-rich waters off the west coast of South America between 5º North and 60º South latitude and east of 120º West longitude, with the major producers including Peru (4,888,730 mt), Chile (3,298,795 mt), and Ecuador (1,186,249 mt); the principal catches include Peruvian anchovy (68.5% of the catch), jumbo flying squid, and Chilean jack mackerel

Pacific Northeast region (Region 67) is the eighth largest fishery in the world, producing 3.6% of the global catch or 2,860,000 mt in 2020; this region encompasses the waters north of 40º North latitude and east of 175º West longitude, including the Gulf of Alaska and Bering Sea, with the major producers including the US (3,009,568 mt), Canada (276,677 mt), and Russia (6,908 mt); the principal catches include Alaska pollock, Pacific cod, and North Pacific hakeRegional fisheries bodies: Commission for the Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna, Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission, International Council for the Exploration of the Seas, North Pacific Anadromous Fish Commission, North Pacific Fisheries Commission, South Pacific Regional Fisheries Management Organization, Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Center, Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission

Government

Country name

etymology: named by Portuguese explorer Ferdinand MAGELLAN during the Spanish circumnavigation of the world in 1521; encountering favorable winds upon reaching the ocean, he called it "Mar Pacifico," which means "peaceful sea" in both Portuguese and Spanish